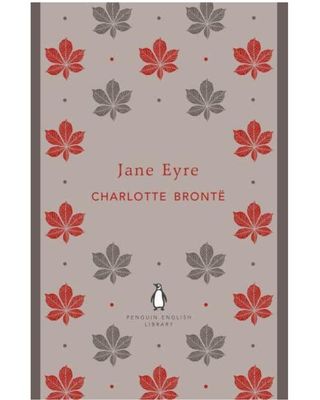

The 35 best books of all time for your must-read list

Our list of the best books of all time include classics from acclaimed authors and novels that made such an impact their influence is still felt today

Sharon Sweeney

The titles featured in this best books of all time list were chosen thoughtfully and with care by woman&home's very own team of bibliophiles. After all, who can truly say what qualities make a book one of the best ever? Is it to do with sales and popularity? Beautiful words or an intriguing plot? A book, fiction or non-fiction, that changed the way we think? We’ve tried to make choices that span genres and centuries and that offer new ideas as well as the showing our love for stand-out classics.

We love to stay up-to-date with the best books of 2022, but this list offers something else. The books we've included below are ones everyone should read at least once in their lifetime - because they will stay with you long after you’ve read the final lines. Whether you're looking for a beautiful love story, a magical adventure, a dystopian exploration of the future, an emotional thrill-ride, or a tale that makes us reflect on our real-world values—there's something for everyone on this list.

So, load up your eReader and prepare to delve into another world with w&h's round-up of the best books of all time, that we believe everyone should read at least once. We’ve listed them in date order, so if you’re looking for modern and contemporary classics, just scroll down the page.

W&H's pick of the best books of all time

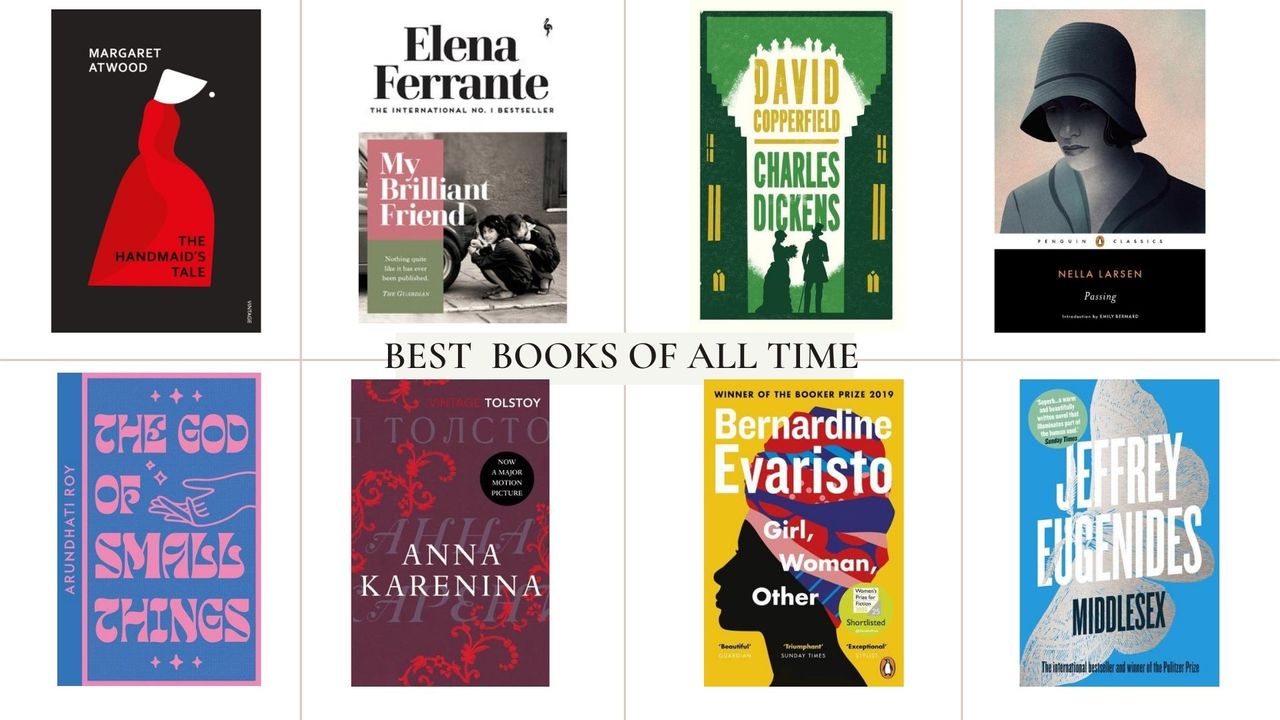

Ask anyone to name a book by Jane Austen and Pride and Prejudice is likely to be their first answer. This 1813 novel is still one of the most popular in all of English literature and the misunderstandings and eventual love between the proud heroine Elizabeth Bennett and aloof landowner Mr Darcy is the template for many of the best romance novels that followed it. It’s far more than just a romance though: Austen’s spiky, witty writing gives us a comment on the fashions and manners of the time, as well as a serious look at the difficult position of women, all told through the stories of Elizabeth’s sisters and her cousin Charlotte. The world has changed since Austen’s day but we still feel the emotions she describes, from the shame of being put down by a bitchy woman at a party to the sweeping, soaring joy of new love.

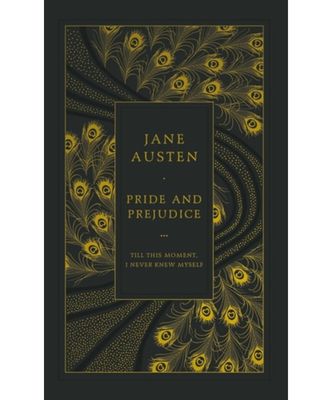

Fraknenstein is widely considered to be the first science fiction book and was written by Mary Shelley when she was just 19 and trapped inside by bad weather on a holiday to the Swiss lakes. Her creations, Dr Frankenstein and his monster, have become instantly recognisable in popular culture and everyone thinks they know the story of Frankenstein, which is what makes the original worth diving into. Dr. Victor Frankenstein becomes obsessed with the idea of forming a new, living person from body parts, but the monster he ends up with is not only hideous but vengeful. Everything Victor loves is lost—and yet we must still have pity on the creature who is desperately lonely, longs for a wife, and craves acceptance that will never come. Like all the best science fiction that followed, Frankenstein uses the strange and unusual to help us examine our own humanity.

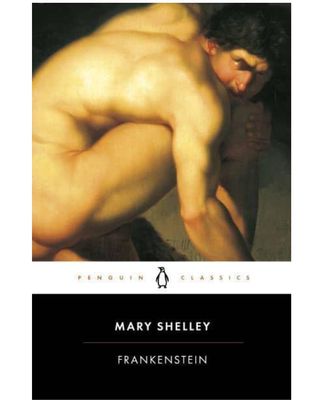

Nuanced, intimate, captivating, and quietly beautiful, Jane Eyre is both widely loved and critically praised, blending romantic and gothic traditions to create an atmosphere all of its own. The story follows orphan Jane from her troubled beginnings in the house of her disinterested uncle, to her position as governess at Thornfield Hall, where she encounters and slowly falls under the spell of the darkly brooding Mr Rochester. Jane was a breakout heroine, she is not outstandingly beautiful or unrelentingly virtuous. She is an everywoman in a situation that changes and shakes her life: a common theme for novels these days, but a new and exciting development in the mid-1800s. Charlotte Brontë also made history by adopting a close first-person narrative voice to tell her story, inviting readers to not only view Jane's life but also be permitted access to her innermost thoughts and feelings. The result is mesmerizing.

No list of great books in English would be complete without a mention of Charles Dickens, and David Copperfield is the novel contains everything Dickens is known for. There are picaresque characters with unusual names, sharp plot twists, intricately described places and a story that goes from a coming-of-age tale to a chronicle of a difficult love affair. It’s also a scathing look at Victorian society, mocking the manners of the middle and upper classes, but saving the real anger for the unjust treatment of poor people, women and the inhabitants of what were then called insane asylums. David Copperfield is also the first book that Dickens wrote in the first person, paving the way for further classics like Great Expectations. The author himself even described the novel as his “favourite child.” If you’re only going to read one book by Charles Dickens, make it this one.

We all know Alice. Most of us enjoyed the story of bored little Alice, who followed a white rabbit with a pocket watch into a hole in the ground and found herself in a strange Wonderland, as children—but it is a classic tale that is well worth a repeat read in adulthood. As well as the perpetual silliness, madcap antics, magical encounters, and joyously nonsense characters, there are moments of deep pathos, too—notably the personification of dementia in The Mad Hatter, who blithely declares: "I'm never sure what I'm going to be, from one minute to the other.” Rereading Alice is a real treat and makes you realise how many of the lines, characters and concepts from the story have become day-to-day references. In the story, Alice encounters food and drink with labels such as ‘drink me’ and ‘eat me’. We feel this book should come with the instruction ‘read me’.

A classic loved by generations of bookish girls and women, who all see themselves in the spirited writer Jo. Little Women chronicles the lives of four sisters in New England during the Civil War. Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy March are being raised in genteel poverty by their mother, Marmee, while their father serves as an army chaplain. An enchanting family drama, Little Women is brimming with life and enduring characters that young (and older) readers have loved for generations. It was a best-seller from the moment of publication, with the first run of 2000 copies selling out immediately, causing Alcott’s publisher to order tens of thousands of copies to be printed. Little Women has never once been out of print, has been translated into more than 50 languages and has been adapted for film, TV and stage many times over.

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The fist line of Anna Karenina still resonates, nearly 150 years after it was first published. The rest of the story still fascinates too. You don’t need to be an aristocrat in Imperial Russia to appreciate the intricacies of love, heartbreak and what it means to be loyal. Beautiful and vivacious, Anna is stifled in her marriage to cold, dull Karenin, although she shines in society and loves her son very deeply. When she meets Count Vronsky the two of them are overtaken by passion. Anna’s new position as a mistress cuts her off from her old life, her son and her friends. A heartbreaking decline begins. Alongside this story of broken promises and broken rules, runs the story of Levin and his tremulous love for Kitty—and their story follows a very different course.

Philip Carey is just nine years old when we join him at the start of this 1915 novel. He has become orphaned after the death of his mother—a seismic event that launches him on a quest to rediscover the happiness he's lost. Along the way, Philip dabbles in art, struggles with a physical disability, studies to become a doctor, battles with faith, and falls both wildly and quietly in and out of love. As with life itself, the book contains moments of great sorrow alongside those of joy. It also looks closely at questions of freedom, do we really wish to be free from society or from our families? After all, as the book itself says “It might be that to surrender to happiness was to accept defeat, but it was a defeat better than many victories.”

The Great Gatsby frequently tops lists of the best fiction books and is often seen as the ultimate American novel. It’s also a byword for 1920s excess, of lavish parties full of flapper girls where the champagne is always overflowing and the guests ever seem to meet the host. But, like Jay Gatsby himself, there’s a lot more to the book than a glamorous surface impression. Written in 1925 by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the book is set in the Jazz Age on Long Island. It’s told from the point of view of Nick Carraway, a young man from a good mid-Western family who has come to New York to work. The much larger house next to his is inhabited by Gatsby, a mysterious millionaire, who is also in love with Nick’s cousin Daisy Buchanan, the woman he lost five years earlier. A lyrical thrill ride that isn't to be missed.

Another novel of 1920s New York, but this time set in Harlem in the city’s north. Passing is both a chronicle and a product of the Harlem Renaissance, the name given to the black cultural boom of music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theatre and political thinking, springing from the neighbourhood. Irene is a light-skinned black woman who occasionally passes as white when it is convenient. On a trip back to her hometown of Chicago she runs into her school friend Clare. Clare has married a white man and let him believe that she too is white. There are further differences, Clare is a fashionable beauty, with little regard for convention. Irene, married to a black doctor, is guarded, sensible and a pillar of intellectual, middle-class Harlem. Although ideas of race and identity underpin the plot, it’s also a tense and page-turning thriller as the lives and deceptions of the two women start to come undone.

Arguably one of the best science fiction books of all time, Brave New World takes place nearly 600 years in the future, where the World Controllers have created the 'ideal' society. Humans are grown inside bottles, then brainwashed to believe certain moral 'truths'. Recreational sex and drugs mean that everyone is a happy consumer. But one man—Bernard Marx—longs to break free. Brave New World has had an interesting reception over the years: it’s been named one of the 100 greatest books of all time by the Modern Library, The BBC, The Observer and more. But it’s also made the American Library’s top 100 of the most-banned books every single year since the list began in 1990. It’s a book with power and a novel that presents a nightmarish vision of how things could be, to make us all reflect on life as we know it now.

Set during the Great Depression, The Grapes of Wrath follows a poor farming family, the Joads, driven from their home in Oklahoma by drought and financial hardship. They set out for California, looking for work, dignity and happiness. The economic conditions of the 1930s mean all three are hard to come by. Steinbeck’s realist book gave a voice to the millions of Americans who had lost their homes and land and been forced to move elsewhere. The Joad family personified the headlines the rest of the country would read over breakfast. The Grapes of Wrath won The National Book Award and The Pulitzer Prize, and when John Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the book was considered to have played a large part. Reading it today is also an interesting reflection on how we currently treat displaced people.

Another American classic and one loved by disaffected teenagers the world over. Set in 1950s New York City, this coming-of-age story centers on Holden Caulfield, who, like Huck Finn, speaks to us straight from the page giving the reader a raw insight into the mind of an adolescent boy. Expelled from school and writing from a mental hospital, he’s caught between the lost innocence of childhood, embodied in his beloved sister Phoebe, and the decidedly unappealing world of adults. Holden experiments with drinking and considers sex, but the majority of his brain is occupied with a search for something authentic and the scorn he feels for ‘phonies’ those who are pretentious or who sell out. The Catcher In The Rye has been described as “the defining work on what it is like to be a teenager” and still sells over one million copies every year.

When a plane crashes on a desert island, the only survivors are a group of schoolboys. At first, the boys are jubilant—there are no adults to tell them what to do. Nonetheless, they start sensibly, voting for a leader, Ralph, building shelters and looking or food. However, the group of boys who gather around the charismatic Jack just want to have fun and hunt. Before long, the boys’ attempt to govern themselves falls apart, and terror sets in. William Golding had served in the British Royal Navy during World War II, an experience which had made him think carefully about the extremes of human behavior. The idea of examining this in a novel about initially innocent school boys was influenced by his work as a teacher. A thought-provoking classic that looks at the end of innocence, what it means to create a civilized society, and human relationships without the confines of the law.

Set during the closing months of the Second World War at a US Army base in Italy, Catch-22 tells the story of disenchanted bombardier Yossarian, who comes up with increasingly outlandish ways to avoid being put in harm's way. The Catch-22 of the title refers to a ludicrous rule that states a man must be insane if he continues to fly dangerous missions, and therefore shouldn't be permitted—but that the truly insane cannot know they are, which means the missions continue. The book shows the madness of war, of any war, even those that seem necessary and morally certain at the time. Yossarian is one of the first of modern literature’s sympathetic anti-heroes: you can’t praise his actions but you do understand them. A satirically genius, funny, disjointed read that requires a certain amount of perseverance from its reader that will really pay off.

Esther Greenwood is a 19-year-old with promise. She is an excellent student and a talented poet with a supposedly bright future ahead of her. Esther, however, cannot find any joy in her achievements or in her dates or her interactions with her friends. “I felt very still and empty,” says Esther. “The way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullaballoo.” Published in 1963 and set 10 years earlier, The Bell Jar is one of the first fictional explorations into how depression really feels for the person experiencing it. The mental health of author Sylvia Plath is now widely talked about and society in general is more open about the topic. But The Bell Jar was radical, blowing open a taboo subject, and doing so with carefully chosen and beautiful words. This is a book that allowed women’s words and women’s creativity, women’s thoughts, feelings and experiences, to start taking up space in society.

Jane Eyre is listed above as a great book, but how would the story look from the perspective of Mr Rochester’s first wife, the “madwoman in the attic”? The Wide Sargasso Sea, from Dominican-British novelist Jean Rhys, offers us a prequel and a new way of seeing things. In Rhys’ hands, madwoman Bertha becomes Antoinette Cosway, a young woman born into a plantation family in Jamaica. She marries an Englishman, Edward Rochester. Her family supply him with a substantial dowry, but give nothing to Antoinette. It’s made clear that Rochester comes to believe that Antoinette, who comes from a white family, has been somehow corrupted by the tropical island she was born on. The Wide Sargasso Sea is a carefully constructed howl of rage, covering slavery, the rights of women and how access to money divides people. As one recent critic put it, “Charlotte Bronte may have started the fire, but Jean Rhys burned down the house.”

This Pulitzer Prize-winning novel was later turned into a film directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Whoopie Goldberg and Oprah Winfrey. It is a powerful and deeply compassionate book. The story is set in the deep American South, where we meet Celie, a young girl born into poverty at a time of segregation. Celie suffers at the hand of her abusive ‘father’ Alphonso. At the start of the novel she is pregnant for the second time and believes Alphonso killed her first baby. Later Celie becomes trapped in an ugly marriage, seemingly unable to escape from a cycle of mistreatment. When she meets the glamorous Shuga and her neighbor, Sofia, everything changes as she discovers the true meaning of female empowerment. The story is told mostly through letters, allowing the reader to piece together the events the characters don’t talk about explicitly. Magnificent storytelling, vividly drawn characters and touching moments make this modern American classic unforgettable, and one of the best feminist books on our list.

Midnight’s Children won the 1981 Man Booker Prize for Fiction. On the 25th anniversary of the Booker Prize, the novel was chosen from all of the other winning titles to be the Booker of Bookers. Charting India's transition into independence and the country's partition through the lively mind of its engaging—and telepathic—protagonist Saleem Sinai, the novel's three separate books blend postcolonial, postmodern, and magical realist literature styles. This might sound extremely serious, but Midnight’s Children is full of rich and varied voices, sounds, smells and colours. It’s also funny, despite the painful events it catalogues. It’s a fairy tale, a work of philosophy, a family saga and a sweeping historical novel. Midnight’s Children doesn’t have the reputation of being an easy read, but there are many readers who fall under the book’s spell ad cannot praise it enough.

This dystopian tale tells of a world where female fertility is too highly prized to be left in the control of individuals. Offred is one of the ‘handmaids’ assigned to produce offspring for high-ranking men in what was once the United States and is now the totalitarian state of Gilead. Defiance means death, but nothing can quell the human spirit—or its desires—completely. Atwood has stated on may occasions that every event or policy contained within The Handmaid’s Tale has already happened at some point: she found the seeds for her dystopia in human history and allowed them to grow into a new shape. The recent television adaptation has drawn in yet more fans, and women dressed in the red cape and white bonnet of the handmaids are now a frequent sight at protests. The world Atwood created still resonates over 30 years later and is arguably more pertinent than ever.

Is love a disease? And is Love In The Time of Cholera even a love story? Columbian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez is one of South America’s most acclaimed writers and this book, set in a fictional country bordering the Caribbean sea, is more accessible than his other classic One Hundred Years Of Solitude. It takes place in a lively but diseased-ravaged city, which smells of both orange blossom and cyanide. As the book opens, Fermina Daza is an older woman married to a doctor. Her husband dies and a man she loved when she was younger, Florentino Ariza, begins to court her again. Florentino has loved Fermina all of his life, despite his many other affairs and romances, but will he win her back? Love In The Time of Cholera exists in a slightly altered reality, where whole love letters can be written on camellia petals and the tropical heat stirs long-held passions.

Toni Morrison is one of the 20th Century’s great writers and any book of hers would sit comfortably on this list. Winner of the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Beloved is set in the mid-1800s in the United States, just as slavery is coming to an end. It is a haunting tale—literally—of the legacy of a horrific period. Sethe made a hard and terrible decision to murder her young child rather than have her grow up as a slave. The baby girl is buried under a tombstone with just one word written on it: Beloved. Now, as times start to change, Sethe and her remaining children are safe in Cincinnati, Ohio. But the family are haunted by the sad and angry ghost of the dead daughter. Motherhood, repressed memory, and identity all come to the fore in this moving tale inspired by a true story.

Richard is from an unremarkable family in an unremarkable California town. When he heads to New England to study at a small liberal arts college, he dreams of ivy covered buildings and tradition. Instead, he falls in with a small group of classics students, dazzled by their old money glamor. The group study with a charismatic professor who instills them with a passion for the darkness and strangeness of ancient Greece. They hold themselves apart from the rest of the college, ignoring the drinking games, toga parties and casual sex the other students enjoy. But that doesn’t mean they are without desires and that they won’t cross moral boundaries. What starts as a lively introduction into a privileged world soon becomes a tense and unusual thriller. The Secret History has been a bestseller for over three decades and gains new fans every year.

This detailed and atmospheric family drama, set in Kerala in southern India, follows twins Rahel, a girl, and Esthappen, a boy. We see them first in 1969 at the age of seven, and in 1993 when the twins find one another again. But they are far from the only characters, the book contains a huge number of stories, sometimes overlapping, sometimes not, in the way that real lives do. Through the family, Arundhati Roy examines India’s caste system and the so-called ‘love laws’ which set strict boundaries on marriages and relationships. The God Of Small Things was Roy’s debut novel and won the Booker Prize in 1997 turning her into a literary superstar. She didn’t publish her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, until 2017 and the frenzy that surrounded it showed what an enduring impact The God Of Small Things had made.

This beautifully written novel reveals how a ‘misunderstanding’ on the part of 13-year-old Briony Tallis in 1935 catastrophically affects the lives of two lovers, her glamorous older sister Cecilia, and handsome Robbie, the housekeeper's son. The interplay of personal and political plays out in a world that is about to be irrevocably changed by World War Two. In this, McEwan questions guilt, atonement, class and how we all construct the narratives of our lives. Briony is our narrator and we know she is capable of lying, but does she deceive us as readers? This is one of the best historical fiction books of all time that will leave you thinking for days (or weeks) afterwards. Atonement is frequently described as one of the best English novels and has sold over two million copies to date. The 2007 film adaptation won several BAFTAs and Academy Awards, including for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Stories about teenage girls being murdered have been told and retold endlessly, and often exploitatively, but what makes The Lovely Bones stand out from the crowd is the fact that the novel's victim is also our narrator. Susie Salmon was just 14 when an eccentric neighbour persuades her to look at a hideout he has built and then brutally rapes and murders her. Susie knows who killed her, and now she is watching from heaven as her family and friends try their best to come to terms with what happened to her and to discover who committed the crime. She also watches how grief reshapes her loved ones in ways she could not have imagined. Far from dwelling on death, Sebold shines a light into darkest corners and illustrates how hope can flourish, courage can prosper, and tragedy can alter perspective in magical ways.

A New York Times bestseller for the best part of two years, this moving novel starts in 1975, where 12-year-old boys living in Kabul, Amir and his best friend Hassan, are desperate to win a local kite fighting tournament - a popular leisure activity in Afghanistan. But that afternoon something happens to Hassan and both of their lives change forever. When Russian forces invade the country, Amir and his parents flee to America -leaving behind their privileged middle class lives. But even as an adult in California, Amir is haunted by what happened to his childhood friend and he returns to his home country, now controlled by the Taliban. As well as tackling weighty themes such as friendship, regret, guilt, and redemption, the novel gives Western readers a valuable insight into Afghanistan and the various cultures within it.

The Curious Incident pulls off a curious trick: from one angle it’s a children’s book with simple sentences, change your perspective and it’s a book for adults, with inferences between every line. At first it was even published with one cover for children and another designed to appeal to older readers. Teenager Christopher Boone describes himself as a “mathematician with some behavioral difficulties” and his manner of expression and the way in which he organises his thoughts suggest he has Aspergers syndrome or high-functioning autism - although author Mark Haddon has said he didn’t set out to show any specific syndrome. Christopher invites the reader along to solve the mystery of who killed next door's dog (the title of the book is adapted from a story about another detective with an interesting mind: Sherlock Holmes). It is a journey that sees Christopher face arrest, uncover secrets, and be reunited with someone he thought was lost to him.

A Pulitzer Prize winner and a four-million strong bestseller, Middlesex follows Cal or Calliope, an intersex man who was assumed to be a girl at birth. It’s also a grand sweeping story taking much of the history of the 20th Century, starting with Cal’s Greek grandparents leaving their village in what was then Asia Minor in 1922 and emigrating to America. The Stephanides family settle in Detroit and their lives are touched by many different events, from the rise and fall of the motor industry to bootlegging during prohibition and inner city riots in the 1960s. But only Calliope/ Cal’s sections are told in the first person, giving the audience an insight into our narrator’s mind as their body changes. Middlesex is very personal, but also shows how our individual actions are affected by world events and the times we live in.

These days, we all recognise the troubled detective standing in the middle of a snow field, or the politician looking out of an architect-designed window into the winter darkness. Scandi-noir is now a standard part of our reading and viewing mix. But it started here, with The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. Stieg Larsson’s book was published in 2005, a year after his death, and rapidly became an international bestseller. Two sequels, also written by Larsson, followed, as did a successful film. The book follows journalist Mikael Blomkvist who is disgraced after losing a libel case. He is hired by an ageing millionaire to investigate the vanishing of the latter’s great niece. Unbeknownst to Blomkvist, Lisbeth Salander, the girl of the title, has also been hired to investigate him. There are many twists and many shocking secrets are uncovered. This is a pacy, interesting read that showed the shadowy side of Sweden to the world and quickly topped best thriller novel lists around the world.

Half A Yellow Sun is set during the Biafran War, which took place in Nigeria in the late 1960s. Twin sisters Olanna and Kainene come from a wealthy and well-connected family, but this cannot prevent their lives - and those of the people around them - from being radically altered by the turmoil. The novel won the 2007 Women’s Prize For Fiction, and has been widely praised for offering a nuanced take on a conflict that, even at the time it took place, hasn’t been well covered by the Western media. There are lots of ideas here - and not just the ones aired by Olanna’s university professor partner Odenigbo and his friends. But they are never allowed to cloud the human experiences and emotions that form the core of the book. Ultimately, this is a story about ordinary people living through history.

Anyone with a small amount of knowledge of British history - or access to Wikipedia - will know how the life of Thomas Cromwell, right hand man of Henry IIIV, ended. Portraits from the time also show Cromwell as a grim and slightly sinister-looking man. So how did Hillary Mantel make this story of the first part of Cromwell’s life so compelling? Compelling enough to win the Booker Prize in 2009, and then again in 2012 for Wolf Hall’s sequel Bringing Up The Bodies? Part of it is that we see the world through Cromwell’s eyes, showing his politician’s reasoning, but also the immense love he has for his wife and children. His fondness for marzipan. His barely contained laughter at the showy hats an acquaintance wears. We follow him from his boyhood on the wrong side of the tracks through to his rise into Henry’s court, dealing with the intrigues spun by Anne Boleyn and High Chancellor Thomas More.

In 2012, it felt as though no-one could stop talking about the mysterious Italian author Elena Ferrente. My Brilliant Friend had been published in both Italian and English and was selling in huge numbers as well as attracting praise from critics. And absolutely no one knew who Ferrante was - not even most the staff at the companies that published her books. The author’s true identity is still a secret, but her books have gone on to find more and more fans. My Brilliant Friend is a story about two girls, Lenu and Lila growing up in a working class district of Naples in the 1960s. It’s a story of female friendship, but one that isn’t afraid to show the bad side along with the good. Neither woman is a perfect heroine, but the honesty is what makes the book fascinating.

Twelve women, mostly black and British, tell their stories. Their tales span years and countries and involve friends, families and lovers. Their voices feel modern and immediate and joyful. This is a book to read if you want to look at how rich the world we live in can be. Literary Prize judges agreed. Girl, Woman, Other was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize, and won a British Book Award, the Women’s Prize for Fiction and shared the 2019 Booker Prize with Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments. The highbrow awards shouldn’t be the reason you do or don’t read it though, as Evaristo’s characters are down-to-earth and concerned as much with what happens in bedrooms and kitchens as they are with thoughts and words. Girl, Woman, Other is a celebration of life.

William Shakespeare had a son and his name was Hamnet. Not much is known about this small boy from long ago, but Maggie O’Farrell creates a life for him, although it’s a life cut short by bubonic plague. We do spend time seeing things from the boy’s perspective, and from his famous father’s, but mostly we see with the eyes of Hamnet’s mother Agnes, known in more conventional histories as Shakespeare’s wife Anne Hathaway. In Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell creates a world that is so complete you feel you can turn away from the action and touch the apples put in storage for the winter. It’s a portrait of life in an English market town in the 16th Century. But it’s also a heartbreaking look at parental grief. A great book club book that will inspire conversation and discussion as the novel explores what happens to a family, a marriage, a person, when a much-loved child dies?

Sign up for the woman&home newsletter

Sign up to our free daily email for the latest royal and entertainment news, interesting opinion, expert advice on styling and beauty trends, and no-nonsense guides to the health and wellness questions you want answered.

Anna is an award-winning journalist with over 20 years experience as a writer and editor. The former Associate Editor of Stylist Magazine, Anna has also written for Elle, The Guardian, British Vogue and the New Statesman.

A self-confessed bibliophile, Anna has hosted live literature events and workshops and is also the host of new author recommendations podcast @readlikeapod.

- Sharon SweeneyGroup Features Director

-

Goodbye premium prices - these M&S slippers have become my new indoor go-to

Goodbye premium prices - these M&S slippers have become my new indoor go-toFor £19.50, these are a wardrobe must-have that you'll reach for daily

By Molly Smith Published

-

Zara Tindall and Princess Eugenie twin in maroon at Cheltenham as they show how occasionwear styling is done

Zara Tindall and Princess Eugenie twin in maroon at Cheltenham as they show how occasionwear styling is doneRoyal cousins Zara Tindall and Princess Eugenie were on the same page with their Cheltenham outfits and their approach is worth following

By Emma Shacklock Published